Tapestry Part IV, Preservation Of Historical Transgender Material

Feel free to visit my Body of Work website.

The Trajectory of Media and the Preservation Of Historical Transgender Material

The advent of the internet had a huge impact on the publishing industry. Most people didn’t see it coming, and some still might not quite believe it, but everything about printed media has changed and will continue to change. The rich cornucopia of books, zines, newsletters, newspapers, and glossy magazines of the mid-nineties—on every conceivable subject—is much diminished and much changed. Even auditory and visual media are different. Compact discs, much lauded as a replacement for vinyl records when they appeared in 1982, are themselves now obsolete, replaced by digital downloads, which are now giving way to streaming services. Movies once available only in theaters became available on VHS video tapes, then DVD, and then, via streaming, to high definition and 4k televisions. America, which used to get its news from trusted newspapers, evening news reports on television, and weekly news magazines like Time and Newsweek, now mostly gets its (dis)information from Russian and Chinese bots on social media. The three big networks, ABC, CBS, and NBC, are still hanging in there, but are overshadowed by the likes of Netflix, Hulu, and HBO.

Books and magazines and newsletters are still being published of course, and there are still CDs and DVDs and evening news broadcasts, but the market has changed drastically. Some older folks cling to older media types—I still enjoy looking through the Sunday issues of The New York Times on occasion—but even elders spent much of their lives with their noses to the screens of smartphones, just like young people. And of course, a few are still listening to music on their 8-track players.

Although there were a number of predecessors with some smartphone features, it was Apple’s iPhone which punched through the wall. Suddenly, smartphones were everywhere, all over the planet. Consider: the first iPhone was released just 15 years ago, in 2007. Anyone younger than twenty has zero experience of a world without powerful internet-connected computers that and be held in one hand and weigh less than five ounces. This far surpasses even the far-out imagination of Chester Gould, the creator of detective Dick Tracy.1

Although there were a number of predecessors with some smartphone features, it was Apple’s iPhone which punched through the wall. Suddenly, smartphones were everywhere, all over the planet. Consider: the first iPhone was released just 15 years ago, in 2007. Anyone younger than twenty has zero experience of a world without powerful internet-connected computers that and be held in one hand and weigh less than five ounces. This far surpasses even the far-out imagination of Chester Gould, the creator of detective Dick Tracy.1

So, excepting retro fads like the resurgence of vinyl,2 we are in a brave new world. Things are not going back to the way they were before, and that means there’s little room for niche magazines like Tapestry. I find that sad, of course, and, perhaps, so do you.

On the flip side, much of trans historical printed material is now available online and instantly retrievable.3

Before the mid-’90s, there was little discussion or interest in collecting and preserving transgender history. I have always attributed that to the necessary focus of trans people on survival and acceptance. When, in 1994, I founded the National Transgender Library & Archive and solicited membership, I had only a half-dozen takers.4 Since 2000, my private collection of trans materials, which I donated to the nonprofit American Educational Gender Information Service,5 has been housed and made available to the public as a special collection of the Labadie Archives at the University of Michigan Library System in Ann Arbor. Although trans materials had long been incorporated in LGB archives, it was often diluted or interpreted as gay or lesbian. The National Transgender Library & Archive was, I believe, the first publicly available trans-exclusive collection in the Western hemisphere.

This issue contained Bobbie Davis’ and Carol Kleinmaier’s article about the history and significance of Female Mimics magazine. It served as an inspiration for this series of articles.

Today, of course, an even larger collection exists at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, and other trans collections6 have become publicly available. Other LGBT archives now contain significant trans content7 and universities are actively seeking transgender historical material.

And them, of course, there’s the Digital Transgender Archive, which was founded in 2016 by K.J. Rawson. In an amazingly short time, the DTA has managed to identify and make available thousands of trans documents. K.J.’s team collaborates with other online sources and serves as a central point of access for their holdings, and in addition, has scanned and digitized an amazing amount of material. I’ve been delighted to find many images generated from magazines and newsletters I sent to the DTA, and I routinely route historic printed matter I chance across to K.J.8

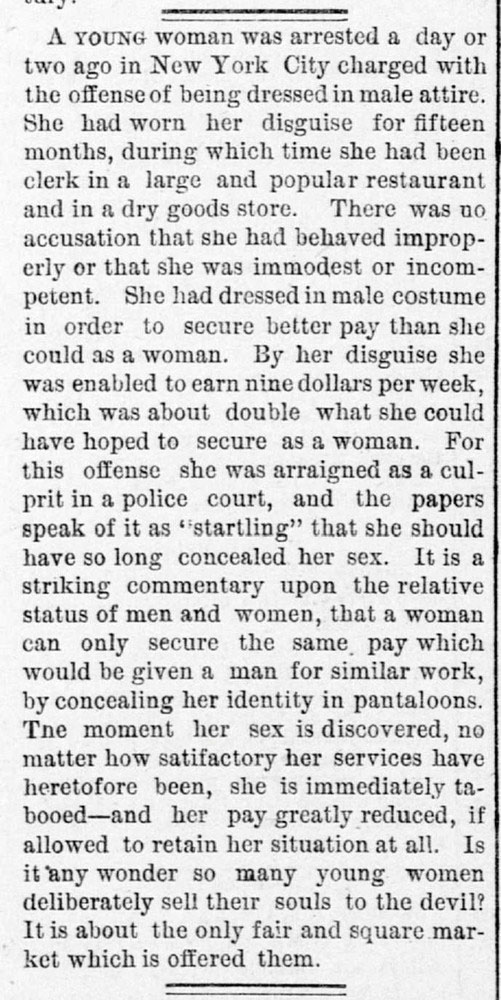

Just one of thousands of images

at the Digital Transgender Archive. Source: St. Paul MN Daily Globe, February 20, 1882.

Not all of our history is available at the DTA—its emphasis is on printed materials before year 2000. There’s little no funding for video and movies, and not every issue of every newsletter and magazine has been located, but the bulk of trans printed history in the last century in much in this century is available there—including a nearly full set of Tapestry magazines. Although I have an almost complete run of hard copies from number 49 on and a few earlier issues, I find accessing them via the DTA faster and more convenient than rifling through a box of magazines. This has proved invariable as I have prepared this series of articles.

Much of trans current history is now playing out on social media and email and text messages. I sometimes wonder how and by whom Facebook and Twitter posts and e-mail will be preserved, but our printed history is secure. That’s important because it facilitates an understanding of what was going on in the transgender community before the public availability of the internet. Even better, it’s available to all of us. I’m proud to have played a small role in making this happen.

Next week, I’ll wrap up this series of articles with a word about why Tapestry and other printed materials were critical to the development of trans communities and, how, for many of us, they affirmed our identities and helped us make sense of our lives. 9

Notes

1 Gould’s Dick Tracy was based upon a real person, a New York gumshoe. A version of Tracy’s futuristic two-way radio wristwatch, introduced in 1946, is now worn by millions of Americans. My Apple iWatch is on my wrist as I type this.

2 By the late 1970s, my friends had all, or almost all, gotten rid of their 45s and LPs. I kept my considerable collection. I had been buying vinyl records since the mid-1960s and was in the habit of haunting the collectibles store The Great Escape in Nashville, where I found a wealth of demos and promotional recordings. I’m glad I kept them all. The new vinyl records are of considerably higher quality than those in the past, but even older records are in demand.

3 I must say that the downsizing of publishers has created new opportunities for aspiring writers. Print-on-demand technologies make it possible to quickly produce a single copy of a book. Amazon.com is flooded with thousands of vanity titles, some of which sell very well, and some of which, alas, don’t sell at all.

5 There is now a biannual conference called Moving Trans History Forward. I presented a keynote at the first, in 2014. You can read about my experience at my website. There’s a link on the page to my Sunday keynote.

6 I founded AEGIS in 1990.

7 For instance, the Louise Lawrence Transgender Archive in Vallejo, California.

8 The Sexual Minorities Archive in Holyoke, Massachusetts holds the papers of the late Leslie Feinberg and much other trans material, and the GLBT Historical Society of California has a wealth of trans material.

9 About six years ago, two of Alison Laing’s daughters drove to my home and left with me their father’s trans material. There were newsletters and magazines dating from the 1980s, and a rich history of Alison’s involvement with (she was a founder) the Philadelphia-based Renaissance Education Association; IFGE (where she served as Executive Director), and Fantasia Fair (now called Transgender Week, where she served as Event Director for quite a few years). I spent the winter sorting and cataloguing Alison’s collection and then sent the collection to the Labadie and the Transgender Archive in Victoria, all by way of the DTA, which scanned the materials. Alison’s early photos were a big hit and soon appeared on Buzzfeed and the Smithsonian Institution’s e-newsletter, which astonished me and made me realize just what an impact the then brand-new DTA was having. Had they gone directly to Ann Arbor and Victoria, they would have been available to the public, but only to those who visited.

Category: History, Transgender History