Interactions With “Public Servants”

When I first came out, I had contacted the IFGE for information about transitioning. I received some pamphlets, most of them reprints from articles appearing in the Tapestry magazine. But there was a very small but important trifold document labeled “Legal Dos and Don’ts for going public Crossdressed.” It was chock full of common sense advice such as: if you’re pulled over dressed, remain seated in the car with hand on the wheel and in plain sight, no sudden movements, do not use false ID, but rather, if your real ID doesn’t match up with how you appear – ‘fess up. Be honest – don’t lie. And never, ever try to pawn off a fake ID as your own. If you are arrested, don’t resist, comply peacefully with the officer and accompany him to the police station.

Other admonitions when interacting with the police would be to not sign any confessions, statements; don’t argue with the officer, don’t try to avoid arrest, don’t try to bribe the officer or give a fake name or address. For what it’s worth, the officer could be led to believe a crime was being committed, or about to be committed

I don’t wonder that interactions that raise suspicions for enforcement authorities may have played a part in the inception of the “carry letter” as a counter-authority that what you are doing is a necessary part of some treatment the crossdressed individual is undergoing. The carry letter has really no legal significance whatsoever; it acts as a professional opinion recommending accommodation and understanding for the police officer, or other authorities, one may come into contact with.

But sometime, just because we are transgender, accommodation and understanding isn’t offered. Just because we are transgender, some public servants seem to go out of their way, to make our way difficult, just because they can. I once met a friend from a support group walking down 12th street. And we stopped to chat and harass cockroaches with pepper spray. A police officer walking across the street at the intersection immediately north, and without stopping, looked at us and yelled, “alright girls, move along!” My friend turned on her heels and started walking the other way. I called after her , “where are you going?” She said “he told us to move.” At that time I really didn’t understand what types of harassment the girls that worked the streets put up with from Philly’s Finest. That was just a minor harassment.

But unfortunately, it can be worse. Sometimes, just because we are transgender, we find ourselves inexorably drawn into dire situations that are way beyond our capacity to control, resulting in unimaginable consequences.

In August 1995, as I was relocating to Philly to begin law school, news arrived from Washington D.C. that a transgender woman name Tyra Hunter had died after being denied emergency medical care at the scene of an automobile accident in which she was seriously injured. The paramedics initially attended to her as they were trained to, but then as The Washington Post reported:

What happened that day remains in dispute and has been the subject of two internal investigations by the D.C. fire department. Residents say that when rescuers began working on Hunter, they were so stunned to discover (s)he was a man that they stopped treating him(her) and laughed and joked before finally taking him(her) to D.C. General Hospital, where (s)he died. (corrections added).

Tyra’s family, who lived nearby, begged the medics to keep treating her, but the rescuer’s amusement continued. Her mother sued the District, which subsequently settled with the family for 1.75 million dollars.

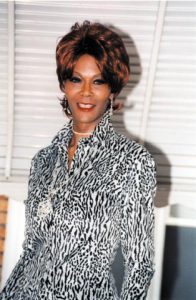

But wait – there’s more. Philly has had its own more sinister scandal involving police interactions with a trans woman. On December 22, 2002, Nizah Morris, a transgender entertainer who was notoriously averse to police interactions, was found laying along Walnut Street between 15th and 16th Streets, bleeding profusely from a head wound shortly after accepting a “courtesy ride” from a female police officer due to her inebriated condition. At some point, it became necessary for the officer to radio for backup. It is speculated that she began sobering up, found herself in the back of a police car and started freaking out and became unmanageable. Backup arrived, and then left. Nizah was found laying between two parked cars She was taken to Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, where she lingered until she was removed from life support and died on December 24, 2002.

The coroner classified Morris’ death as a homicide, because her head wound was not one that would occur by stumbling and hitting the curb. The official Police Advisory Committee investigation as to the police involvement in Morris’s death was, not surprisingly, inconclusive. Morris’ sister and a former police officer herself, said she thinks she knows what happened:

“When I went to the morgue and saw the wound on Nizah’s head, it was a wound I’d seen many times. Clearly, she was hit by the butt of a gun.”

PGN reporter Timothy Cwiek was doing his own investigation into the Nizah Morris case, and I got involved in his investigation by filing some FOI requests for recordings of radio dispatches and transcripts of, police chatter and chasing them through the court system. Tim acquainted me with the term ”Temple Turban” If you are at all familiar with the police lingo, you know what happened to Nizah, just as much as her sister knew. Tim went on to receive the Society of Professional Journalists Sigma Delta Chi Award. Nizah’s family settled with the City for $250,000.

For me, I contented myself by taking in the pile of flowers that would appear over the Christmas season for several years near the location where Nizah was found dying years earlier, just below my office window.

There is a reason we as a community observe a Day of Remembrance – to keep the memories of women like Tyra and Nizah alive.

Like to make a comment? Login here and use the comment area below.

Category: Transgender How To