A History of Tapestry Magazine, Part 1

© 2022 by Dallas Denny

Note: Producing this history was greatly facilitated by the Digital Transgender Archive, which provides free downloads of most issues of Tapestry. I possess most of the issues not archived in the DTA, but neither I nor DTA Director K.J. Rawson have never seen the first eight issues. I have to say, someone’s doctoral dissertation awaits in analyzing this transgender treasure trove. How interesting it would be to see graphs over time of page counts, numbers of advertisers, pages devoted to personal listings, and other data showing tracing the eventual development of a two-page newsletter into an internationally-distributed glossy magazine. What follows is but a first step toward unraveling the history of this fascinating publication.

A History of Tapestry Magazine

Part I

100 Issues, 30 Years

By Dallas Denny

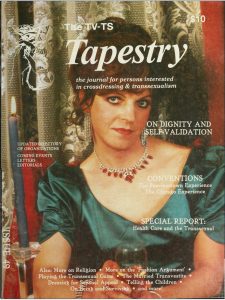

Throughout its thirty-year run from 1978 through 2008, Tapestry—first a newsletter, and then a magazine—was an iconic and respected publication. It began as TV Tapestry, the newsletter of Boston’s newly-created Tiffany Club of New England, and ended at number 115 as Transgender Tapestry, a magazine with glossy pages and four-color covers. At Tapestry’s peak, circulation was north of 10,000 copies, and it was mailed to subscribers, exchanged for newsletters of transgender organizations, and displayed on shelves in bookstores around the world.

For more than 20 years, Tapestry was the go-to publication for many transgender people in the United States. Its listing of support groups and helping professionals, which was eventually included in every issue, was lifesaving for me, as it led me to the support and information for which I had been searching my entire life. How curious that I would one day wind up as Editor-in-Chief! Beginning in 2000 and ending in 2005, I was responsible for the content of 23 issues—issues 89-112.

Tapestry began as the in-house publication of the Tiffany Club (now the Trans Community of New England). The first club meeting was held in December, 1977 in New Hampshire, in the home of the late Merissa Sherill Lynn.

The names, Tiffany and Tapestry, were chosen with great care. Both have deep meanings that symbolize the very nature and mission of the organization…. The word Tiffany derives from the word Theophany, the divine manifestation of God to man…. The name, Tapestry, was chosen for the newsletter because it represented the ‘weaving’ of all orientations into one. The intent of the newsletter, later magazine, was to weave our community and society as a whole, into one. From the very beginning, the Tapestry newsletter was addressed to the entire Crossdressing community, not just the Tiffany Club. Events taking place in other organizations were reported along with local events….

Merissa edited the first 63 issues of Tapestry. Under her stewardship, the name evolved from simply “Newsletter” to TV Tapestry to The Tapestry to TV-TS Tapestry. The page count increased from two to, at some times, more than 150. The first issues were typed and photocopied and had no illustrations. Issue 13 saw the first use of a graphic—a rose, the symbol of TCNE; it was pasted in, as the text was still clearly generated on a typewriter. The first photos appeared in issue 14, and illustrations gradually became a significant and eventually essential part of the content.

Tapestry, at first indistinguishable from other trans community newsletters of the day, became ever more broad-based and sophisticated, and Merissa was soon covering the waterfront by reposting news articles, publishing articles by various writers, providing lists of resources, printing letters to the editor, and accepting business and personal ads.

As the issue numbers climbed, Merissa’s simple newsletter became more and more like a magazine, until suddenly it was one. For me, issue 33 hits that sweet spot. It was the first issue to include a price on the cover—three dollars and fifty cents, applied by a rubber stamp at the last minute—but a sales price nonetheless. The next issue doubled the page count to 50, and the issue after that was the first to include a table of contents. By issue 40, the cover price had increased to ten dollars.

As magazine status was achieved, more and more advertisers appeared on Tapestry’s pages and the list of resources grew longer. So, too, did personal ads. Personals debuted in a modest way in 1980, in issue 24. By issue 50, in 1987, they had increased to nearly 40 pages. Issue 50 also marked the change of the organizational imprint from Tiffany Club of New England to International Foundation for Gender Education. In an editorial column in that issue, Merissa talked about her personal history and her desire to form a “network of effective support groups servicing the entire spectrum of our community (not an isolated segment of it), and an umbrella organization that would provide a unifying factor without dominating anyone or any group, or dictating policy.” This was the same motivation that had led Merissa and her supporters to form TCNE in 1977. Merissa felt that TCNE, which functioned as a regional group, wasn’t up to the job. I haven’t yet sussed out coverage in the Tapestry archives of the history of the formation of IFGE, but it happened primarily in Provincetown, on Cape Cod, during Fantasia Fair week, and it’s probably described in one or another of the issues. The earliest mention of IFGE I found in Tapestry was in 1986’s number 48.

Tapestry number 49 was the first with a four-color cover and the first to feature a photograph of an actual person.

Before the formation of IFGE, the largest and most influential trans organization was Tri-Ess, the Society for the Second Self, which existed to support heterosexual crossdresser and their female partners. Unfortunately, Tri-Ess’ unnecessary exclusion of gay crossdressers and transsexuals, largely kept those two segments of the community separate and distinct from groups for straight crossdressers. Most support organizations served one group or the other and, before the formation of IFGE and Holly Boswell and Jessica Britton’s Phoenix Transgender Support Group in Asheville, North Carolina (both in 1986), there was little mingling or cross-communication between these populations. The advent of IFGE’s Coming Together Convention in 1987 changed that, and soon there was ongoing discussion about language, community, and legal issues at the convention and in correspondence in the pages of Tapestry and more than 100 newsletters around the U.S. It was out of this back and forth and in particular the publication of Holly Boswell’s 1991 ground breaking article The Transgender Alternative simultaneously in Tapestry and my own Chrysalis Quarterly that the term transgender came into common use.

With issue 64, in 1993, Vivian D. Allen became editor-in-chief. I know little about her (and would appreciate hearing the recollections of those who do), but under her guidance, the magazine continued to evolve. My best guess is that she was an excellent editor.

With issue 74, in 1995, noted science fiction and nonfiction author Jean Marie Stine became editor-in-chief and TV-TS Tapestry was renamed Transgender Tapestry. For four issues, the front cover, which since 1986’s issue 49 had featured trans women, spotlighted celebrities like Patrick Swayze and Nathan Lane before reverting to covers depicting trans women—this time in groups.

For issue 83, in 1998, Nancy Nangeroni, at that time Executive Director of IFGE, was listed as co-editor, along with Mykael Hawley and Matthew S. Carlos. Mykael and Matthew, minus Nangeroni, co-edited issues 84-88. Mykael was art director for all six issues. Under their oversight, Tapestry took a dark turn, both in appearance and in content. I remember a fiction piece with a torture scene in which a trans woman’s fingernails were pulled out with pliers—but worse, the sans serif font Hawley used in the main text made the magazine, at least for me, unreadable. Jamison Green is a wonderful writer, and I ordinarily hang on his every word, but I was utterly unable to read his piece The Art & Nature of Gender in issue 96; that font tuned my eyes out and my brain off to the point that I never, I’m sorry to say, finished Jamison’s piece—or read anything else in the issue. I did look at the pretty pictures, however. This is, of course just my opinion; the letters to the editor in issue 89 are laudatory.

In 1999, my friend and IFGE board member Terry Murphy visited my home and told me the board had decided that rather than have salaried employees at the IFGE offices, future editors and art directors would work on a contract basis. I, Terry told me, was the board’s first choice as editor-in-chief. I accepted. It was my first-ever paying transgender gig; until then, I had been undertaking as much activism as I could afford.

My first issue was number 89, which appeared in the spring of 2000. My last issue was 110, printed in the fall of 2005. I’m proud of my run of twenty-one issues.

My favorite was Tapestry 100, the centennial issue, published in 2002. I took advantage of the round number to take a retrospective look at what had happened in the transgender world over the previous fifty years. It had been, after all, fifty years since news of Christine Jorgensen’s change of sex, as it was then called, had rocked the world. It was the first time I worked on Tapestry with an art director who I felt fully understood and could fully realize my vision for the graphic design of the magazine. I love the cover, which is a montage of photographs of Jorgensen, and the closeup bleed of her face across pages four and five. I continue to be impressed by the historical section on pages 24 through 37. Thank you, Jessica Johnson, for your marvelous work! Thanks also to Associate Editor Donna Cartwright, Contributing Editors kari Edwards, Miqqi Alicia Gilbert, Monica Helms, and Andrew Matzner, to Mariette Pathy Allen for generously allowing the use of her photographs over Tapestry’s entire run, to Art Directors Larissa Glasser, Nicole Veneto, Kim Titcomb, and Dave Bryant, and to the many people who contributed to the twenty-one issues over which I presided.

IFGE Executive Director Denise Leclair edited the last five issues of Transgender Tapestry. The magazine had been in financial distress for some time, and, after issue 115, quietly vanished. It and IFGE were suddenly just gone, and no one in the community, or so it seemed to me, noticed.

Stay tuned for Part II, in which I describe the complexities of having a personals section, and Part III, in which I myself get personal as I describe my experiences with the magazine. And who knows—perhaps I’ll generate some graphs about page counts, numbers of advertisers, and the length of the personal section.

Works Cited

Aine, Rebecca. (2004). A Brief History of Trans Community of New England. https://tcne.org/a-brief-history-of-trans-community-of-new-england/. Accessed 14 November, 2022.

Lynne, Merissa Sherrill. Virginia. (1987). TV-TS Tapestry, p. 8.

On the other side of the fence, confidentiality requirements of the gender clinics also kept transsexual people isolated and alone. Gay crossdressers often found safe space at gay clubs but in some cities fear of the police kept them out when dressed. The entertainers would often be required to change into street clothes before leaving for home.

Boswell, Holly. (1991-1992, Winter). The transgender alternative. Chrysalis Quarterly, 1(2), 29-31 and TV-TS Tapestry, 58, 31-33. (1991).

Category: History